This is Chapter 8 of my new book, working title “The Industry Playbook: Corporate Cartels, Corruption and Crimes Against Humanity” that is being published online chapter by chapter.

By infiltrating existing institutions, Big Tobacco was able to spread its message through them. In some cases, this involved borrowing the credibility and authority of such places. Or at the very least Big Tobacco would aim to slow down institutions from taking harsher positions against them.

Let’s start with the American Medical Association (AMA). As we’ve already seen, Big Tobacco advertised heavily within the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA). Yes, the advertisements were there to influence the doctors and scientists that read the journal. But even more important was to establish the financial relationship between Big Tobacco and the AMA. This wasn’t just about advertising but gaining influence over editorial content.

Morris Fishbein singlehandedly led the AMA for many years. Robert N. Proctor, professor at Stanford, wrote about such connections. “Dr Morris Fishbein of Chicago was another prominent defender of the industry. As iron‐fisted editor of JAMA, Fishbein helped stave off efforts to have the journal refuse tobacco ads and, in the mid 1950s, received about $100000 from Lorillard to write industry‐friendly articles on smoking and health. Fishbein also helped place ads for Kent cigarettes in medical magazines…the man should also be remembered as author of a 1954 review of tobacco and health hazards, contracted by Doubleday with financial backing from Lorillard. The makers of Kent cigarettes—with its ‘micronite’ asbestos filter—paid Fishbein tens of thousands of dollars to write [a] book.”

It was this cozy relationship that eventually forced Fishbein out. “Fishbein was actually booted from his position as JAMA editor a year after his editorial, partly for his refusal to limit cigarette ads in the pages of JAMA…In 1953 JAMA’s new editors announced that they would no longer publish tobacco ads of any kind, by which time Fishbein was receiving tens of thousands of dollars per year to front for the industry.”

Through the revolving door Fishbein went. In the 60’s and 70’s he continued to work for Lorillard.

That shows what one man, holding sway over one large institution can do. And even though they stopped advertising, that doesn’t mean the AMA came out strong against tobacco. Even as late at 1965, one year after the Surgeon General’s report, the AMA resisted taking a position against smoking.

CEO of the AMA, F.J.L. Blasingame stated, “it is our opinion that the answer that will do most to protect the public health lies not in labeling…but in research.” The phrase “more research is needed” was the exact PR message of Big Tobacco.

They finally took a stand, launching a war against smoking, in 1972. Not exactly on the forefront of the biggest medical killer out there from the most powerful medical organization, at the time, in the world.

Part of the reason that institutional infiltration worked had to do with the size of such organizations. Brandt writes, “The fight for tobacco control ordinances demonstrated the possibilities of grassroots public health advocacy. Single-issue advocacy groups were in a far better position to take up the fight than the traditional voluntary health organizations like the American Cancer Society and the American Heart Association. The latter had complex constituencies and philanthropic and educational missions that led to an inherent conservatism; they sought to avoid political controversy that could alienate not only smokers, but donors from tobacco-growing states. The new organizations reveled in controversy, deliberately seeking media attention to sustain their cause.”

For instance, in 1957, scientists from American Cancer Society, American Heart Association, National Cancer Institute, and the National Heart Institute looked at the data and concluded: “The sum total of scientific evidence establishes beyond reasonable doubt that cigarette smoking is a causative factor in the rapidly increasing incidence of human epidermoid carcinoma of the lung…The evidence of a cause-effect relationship is adequate for considering the initiation of public health measures.”

But these scientific positions didn’t always translate into policy, based on the controversy, constituency and funding involved. (In a bit of irony, the American Heart Association would hire Hill & Knowlton in 2004 and received tremendous backlash for the PR firm’s role in tobacco which causes heart disease.)

Some of the institutional outreach was more defense than offense, seeking to do damage control and soften anti-tobacco positions. In 1963, Little and the TIRC attempted to shape the Surgeon General’s Advisory Committee through the committee’s medical coordinator, Peter Hamill. They were ultimately unsuccessful in doing this, but they tried.

I think the World Health Organization (WHO) provides one of the best examples of institutional infiltration. In 1995, the World Health Assembly, WHO’s governing body, began looking into the possibility of an international treaty on tobacco control. In May of 1996, the World Health Assembly unanimously passed a resolution for the director-general of the WHO to develop a framework convention, a type of multilateral treaty, for tobacco control.

And finally, in May 2003, the 192 member nations of the WHO unanimously adopt the FCTC (Framework Convention of Tobacco Control), which was the WHO’s first ever multilateral treaty. More on the effects of that later.

When I was doing research on the history of the WHO, I found a document called Tobacco Company Strategies to Undermine Tobacco Control Activities at the World Health Organization.

This was put together internally at the WHO by the Committee of Experts on Tobacco Industry Documents in July 2000.

This 260-page report is extremely revealing, sharing how the WHO was infiltrated and influenced by Big Tobacco. Here are just a few quotes from inside:

- “Evidence from tobacco industry documents reveals that tobacco companies have operated for many years with the deliberate purpose of subverting the efforts of the World Health Organization (WHO) to control tobacco use. The attempted subversion has been elaborate, well financed, sophisticated, and usually invisible.”

- “In one of their most significant strategies for influencing WHO’s tobacco control activities, tobacco companies developed and maintained relationships with current or former WHO staff, consultants and advisors. In some cases, tobacco companies hired or offered future employment to former WHO or UN officials in order to indirectly gain valuable contacts within these organizations that might assist in its goal of influencing WHO activities. Of greatest concern, tobacco companies have, in some cases, had their own consultants in positions at WHO, paying them to serve the goals of tobacco companies while working for WHO. Some of these cases raise serious questions about whether the integrity of WHO decision making has been compromised.”

- “In several cases, tobacco companies have attempted to undermine WHO tobacco control activities by putting pressure on relevant WHO budgets. Tobacco companies have also used their resources to gain favor or particular outcomes by making well placed contributions.”

- “Documents in this study illustrate that tobacco companies utilized a number of outside organizations to lobby against and influence tobacco control activities at WHO including trade unions, tobacco company created front groups and tobacco companies’ own affiliated food companies.”

- “Much of the Boca Raton Action Plan [created at a secretive Big Tobacco meeting] involved the creation or manipulation of seemingly independent organizations with strong tobacco company ties. The documents show that some of these organizations such as LIBERTAD, the New York Society for International Affairs, the America-European Community Association and the Institute for International Health and Development, were used successfully to gain access to dozens of national and world leaders, health ministers, WHO and other United Nations agency delegates.”

Once again, propaganda and influence are actually less about influencing the public directly but instead through all manner of professionals. This includes influencing organizations to make use of their authority ideally to advance your agenda. If that doesn’t work then seeking out to undermine their authority instead.

By necessity, this complicates matters significantly. Yet it is exactly a group like Big Tobacco, who has the necessary money and people, that is able to afford to play this game. The complicated web they weave involves front organizations, consultants, donations and so much more involved.

Because this is more complicated most people are not able to see it happening. The WHO had to look deep at themselves in this area to come to terms with the specifics of how they were infiltrated. That’s a rare thing! (Unfortunately, these same exact tactics are used even more successfully by other industries with the WHO and other large organizations.)

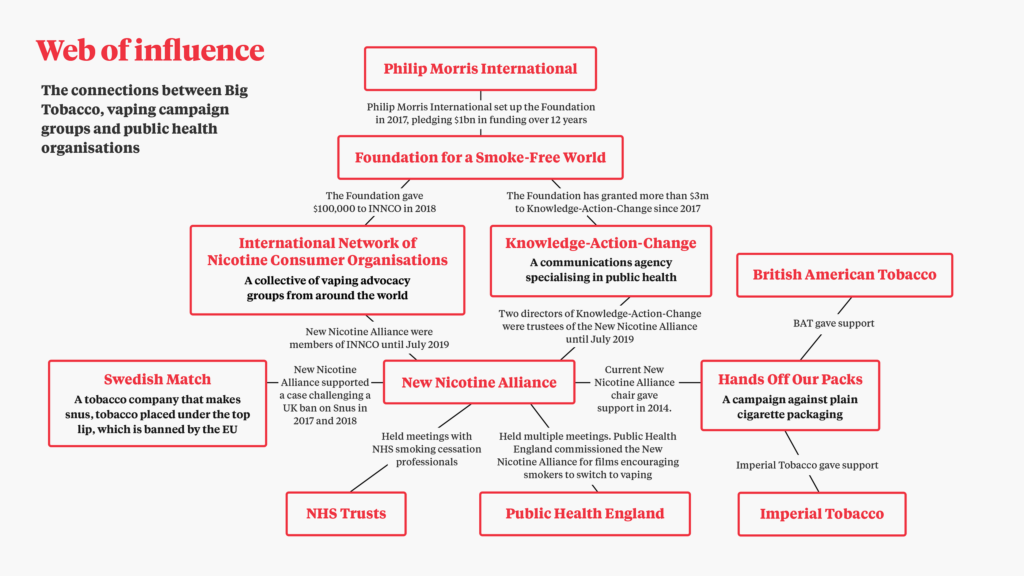

These same tactics of infiltrating institutions and setting up front groups are still being used to this day. A 2020 article by The Bureau of Investigative Journalism shows how Phillip Morris, British American Tobacco and others were able to use front groups to ultimately influence NHS and Public Health England.

A picture is worth a thousand words. Here you see the combination of advocacy front groups being used to infiltrate bigger and more powerful scientific and public health institutions. Webs of influence are a main method of the playbook.

Key Takeaways on Infiltrating Institutions

- Advertising, whether in journals, on TV, or elsewhere is a useful step in gaining some influence over editorial content.

- The largest and most powerful medical association, the AMA, was firmly under the financial influence of Big Tobacco for decades. They promoted cigarettes, and even when that stopped, refused to stand against them, echoing the PR line of Big Tobacco. They only came out against smoking in 1972, hardly at the forefront of the science.

- Even when large organizations took scientific stands, it often didn’t translate into policy due to complex reasons of constituencies, politics, and influence.

- Big Tobacco attempted to influence the Surgeon General’s committee through Peter Hamill. While this attempt was unsuccessful, it was just one of many such attempts.

- The FDA tried hard to put tobacco under its jurisdiction in 1996, but Big Tobacco was able to delay this regulation until 2007.

- A report from the WHO looked at how they were infiltrated and subverted by Big Tobacco including by paying consultants, advisors and other officials that worked for or with the WHO, by the use of political pressure, lobbying and more.

- The Boca Raton Action Plan, created at a secretive Big Tobacco meeting, relied primarily on using various advocacy front groups to help influence and infiltrate institutions. These complicated “webs of influence” are an industry playbook mainstay.

Please leave any comments or questions below. Feel free to share it with anyone you’d like.

Links to all published chapters of The Industry Playbook can be found here.

You can also support this project with a tip.