This is Chapter 27 of my new book, working title “The Industry Playbook: Corporate Cartels, Corruption and Crimes Against Humanity” that is being published online chapter by chapter.

The story of leaded gasoline is far worse than that of cigarettes. But fewer people seem to be aware of any of the details of this escapade of big industry. You and I have lead still in our bones to this day because of the actions of the people shown here.

In 1921, Thomas Midgley Jr., an engineer working at General Motors (GM), discovered that adding tetraethyl lead (TEL) to gasoline improved engine performance by having an anti-knock effect.

Midgley’s boss was Charles Kettering, the head of research at GM. The president and CEO was Alfred P. Sloan. Their names would go on to be best known today as being on the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. (What goes on there and in the wider cancer industry will be discussed later.)

It wasn’t just GM involved. By 1920, the du Pont family owned more than 35 percent of GM shares. So Du Pont was intimately involved from the beginning. We’ll also hear more about Du Pont in a later chapter.

Standard Oil of New Jersey was also involved. They merged with Standard Oil of New York becoming what is known today as Exxon, the largest player of the original monopoly of Standard Oil that had been broken up.

These companies and their researchers said that the lead from gasoline wouldn’t harm anyone. Some of them probably believed that was the case. The common refrain, that the amounts used would be too small to hurt anyone, was the company line.

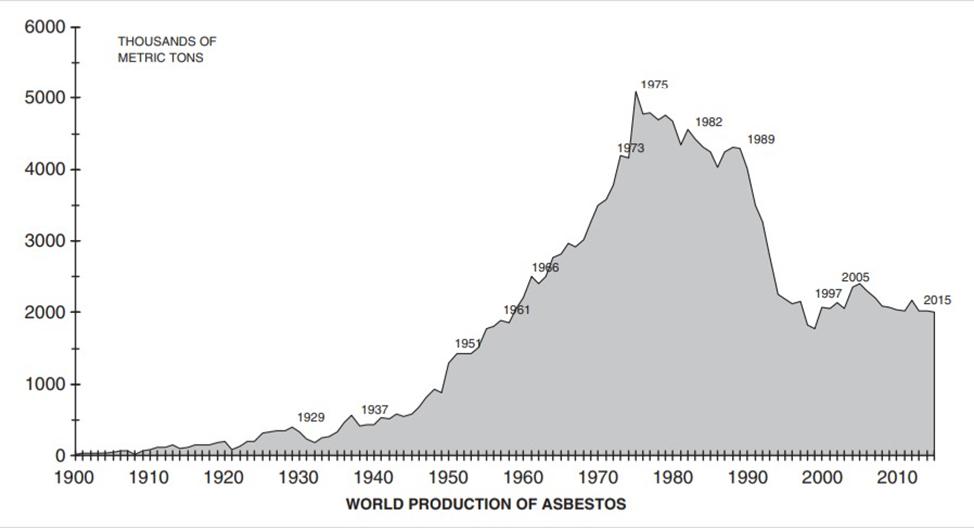

The result was that massive amounts of lead were spread across the entire world through the use of cars and other vehicles.

Jamie Lincoln Kitman won an investigative reporting award for his Nation article on leaded gasoline, which much of this chapter stems from. He will be quoted throughout.

Dangers of Lead

The dangers of lead were already known back when they started using it. Even the ancient Greeks thousands of years ago where aware of what lead could do.

Lead is linked to lower IQ, heart disease, cancer, many other diseases, and even rises in violent crime and other behavioral issues.

It easily contaminants the air, water and soil. This leads to bioaccumulation as it does not break down, being one of the periodic elements. The estimated 7 million tons of lead burned in gasoline are now spread throughout the environment. A 1983 report by Britain’s Royal Commission on Environmental Pollution stated that “it is doubtful whether any part of the earth’s surface or any form of life remains uncontaminated by anthropogenic lead.”

A 1985 EPA study estimated 5,000 Americans died annually from lead-related heart disease before the phase-out occurred.

Leaded gasoline’s eventual USA banning lead to a drop in mean blood-lead levels of 75 percent. Understand that between 1927 and 1987 every single person was exposed to toxic levels of lead. This was most damaging to children, including babies in the womb.

But other countries continued to use it longer. Venezuela sold only leaded gasoline until 1999. Sixty-three percent of newborn children contained levels of lead in excess of the safe levels established by the government there.

An estimated 90% of the lead in the atmosphere is from gasoline. Other areas like mining and lead based paints contribute a minor amount in comparison.

All these dangers were denied and covered up by industry from the very beginning.

They Knew the Dangers of Lead When They Started Using TEL

Tetraethyl lead was first discovered by a German Chemist in 1854. It wasn’t used commercially because of “its known deadliness.” For over sixty years, it had no use until Midgley found one for it.

In March 1922, a Du Pont executive, Pierre du Pont described TEL as “a colorless liquid of sweetish odor, very poisonous if absorbed through the skin, resulting in lead poisoning almost immediately.”

William Mansfield Clark, lab director in the US Public Health Service, had written the assistant Surgeon General A.M. Stimson when Du Pont’s production first got underway. He said TEL was a “serious menace to public health” and that reports were coming in that “several very serious cases of lead poisoning have resulted” from the plant’s production.

In turn, the US Surgeon General, H.S. Cumming wrote to Pierre du Pont in December 1922, “Inasmuch as it is understood that when employed in gasoline engines, this substance will add a finely divided and nondiffusible form of lead to exhaust gases, and furthermore, since lead poisoning in human beings is of the cumulative type resulting frequently from the daily intake of minute quantities, it seems pertinent to inquire whether there might not be a decided health hazard associated with the extensive use of lead tetraethyl in engines.”

Midgley himself was suffering from lead poisoning in 1923. “After about a year’s work in organic lead I find that my lungs have been affected and that it is necessary to drop all work and get a large supply of fresh air,” he wrote.

Leaded Gasoline was Never Needed, in fact Inferior from the Very Beginning

Not only were the dangers known, but the benefits weren’t even that great. Other additives to gasoline functioned in much the same way, in fact many are superior. Ethanol, better known as alcohol, is used instead of lead today.

Ethanol could be used back then. An article in Scientific American said in 1918 that, “It is now definitely established that alcohol can be blended with gasoline to produce a suitable motor fuel.”

Unfortunately, ethanol had a fatal flaw as far as industry was concerned. It couldn’t be patented. This and other additives were suppressed and smeared by the industry.

In fact, ethanol might have been used to power cars completely without oil involved at all! Kitman wrote, “In 1907 and 1908 the US Geological Survey and the Navy performed 2,000 tests on alcohol and gasoline engines in Norfolk, Virginia, and St. Louis, concluding that higher engine compression could be achieved with alcohol than with gasoline. They noted a complete absence of smoke and disagreeable odors.”

Henry Ford’s Model A car could be adjusted from the dashboard to run on gasoline or ethanol. But this simply wouldn’t do for the growing oil industry.

In 1920, Midgley filed a patent for alcohol and cracked gasoline as antiknock fuel. He told a meeting of the Society of Automative Engineers, “Alcohol has tremendous advantages and minor disadvantages.” The benefits included “clean burning and freedom from any carbon deposit…[and] tremendously high compression under which alcohol will operate without knocking…Because of the possible high compression, the available horsepower is much greater with alcohol than with gasoline.”

Although this process was patented, ethanol itself could not be. Despite its earlier discovery, TEL could be patented, and it would be owned by GM.

That Midgley has earlier patented an alcohol gasoline process would later be denied. In August 1925, Midgley lied to a meeting of scientists, “So far as science knows at the present time, tetraethyl lead is the only material available which can bring about these [antiknock] results, which are of vital importance to the continued economic use by the general public of all automotive equipment, and unless a grave and inescapable hazard rests in the manufacture of tetraethyl lead, its abandonment cannot be justified.” This lie helped to protect the cash cow that TEL became.

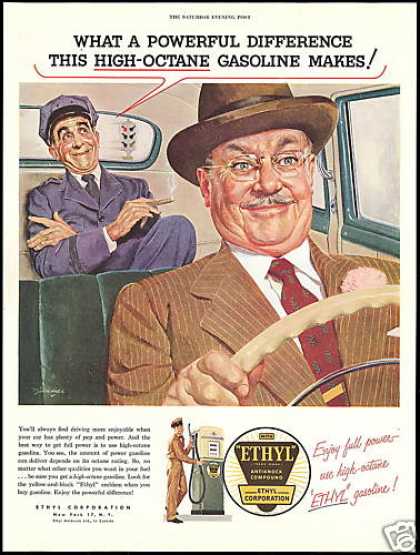

TEL was marketed as Ethyl with no mention of lead at all. This is because of the negative connotations that lead justifiably carried. And this named happened to be curiously close to ethanol.

Standard Oil of New Jersey Gets in on the Game

Leaded gasoline swept the nation. So much so that GM couldn’t keep up with production.

In 1924, Standard Oil of New Jersey developed and patented a better manufacturing technology for TEL. They formed a joint venture with GM called the Ethyl Gasoline Corporation.

August of that year, they began production at its Bayway plant in Elizabeth, New Jersey. Du Pont engineers had expressed serious concerns about the safety of this facility. Yet this information was not acted on.

Kitman writes, “On October 26, 1924, the first of five workers who would die in quick succession at Standard Oil’s Bayway TEL works perished, after wrenching fits of violent insanity; thirty-five other workers would experience tremors, hallucinations, severe palsies and other serious neurological symptoms of organic lead poisoning. In total, more than 80 percent of the Bayway staff would die or suffer severe poisoning. News of these deaths was the first that many Americans heard of leaded gasoline–although it would take a few days, as the New York City papers and wire services rushed to cover a mysterious industrial disaster that Standard stonewalled and GM declined to delve into.”

Some other deaths and incidents had occurred at other TEL plants as well earlier, but these were more successfully covered up from public knowledge.

Standard’s medical consultant, J. Gilman Thompson helped to cover it up stating that, “Although there is lead in the compound, these acute symptoms are wholly unlike those of chronic lead poisoning such as painters often have…There is no obscurity whatever about the effects of the poison and characterizing the substance as ‘mystery gas’ or ‘insanity gas’ is grossly misleading.”

These events led to Philadelphia, Pittsburgh and all of New Jersey banning leaded gasoline. Meanwhile, it continued to be sold elsewhere.

Regulating the Regulators

To help with the coverup, GM contracted the US Bureau of Mines to investigate the deaths. “Even by the lax standards of its day, the bureau was a docile corporate servant, with not an adversarial bone in its body. It saw itself as in the mining promotion business, with much of its scientific work undertaken in collaboration with industry,” writes Kitman.

The Ethyl Gasoline Corporation had veto power over what this agency wrote, the contract stating, “before publication of any papers or articles by your Bureau, they should be submitted to them for comment, criticism, and approval.”

In November 1924, the Bureau of Mines report was released. It only contained limited animal testing which found no problems with TEL.

The New York Times ran with the front-page headline “No Peril to Public Seen in Ethyl Gas/Bureau of Mines Reports after Long Experiments with Motor Exhausts/More Deaths Unlikely.”

This report and the surrounding press not only helped to allay fears of dangers to workers, but the overall danger of leaded gasoline.

Yandell Henderson of Yale attacked the report quite presciently. That while they had “investigated the danger to the public of acute lead poisoning,” they had, “failed even to take into account the possibility that the atmosphere might be polluted to such an extent along automobile thoroughfares that those who worked or lived along such streets would gradually absorb lead in sufficient quantities to poison them in the course of months.” Eventually, “conditions will grow worse so gradually and the development of lead poisoning will come on so insidiously (for this is the nature of the disease) that leaded gasoline will be in nearly universal use and large numbers of cars will have been sold that can run only on that fuel before the public and the Government awaken to the situation.” In a summation that describes American policy quite well he wrote, “This is probably the greatest single question in the field of public health that has ever faced the American public. It is the question whether scientific experts are to be consulted, and the action of Government guided by their advice, or whether, on the contrary, commercial interests are to be allowed to subordinate every other consideration to that of profit.”

Still, such incidents led to the voluntary withdrawal of Ethyl for a limited time in May 1925. But this may have been part of its public relations strategy and nothing more.

Further investigation would take place. Charles Kettering himself, as well as executives from Standard and Du Pont paid a private visit in 1924 to Surgeon General Hugh Smith Cumming. They requested the Public Health Service investigate TEL, holding private hearings.

This special committee found “no good grounds” for prohibiting leaded gasoline in January 1926. Their report found, “So far as the committee could ascertain all the reported cases of fatalities and serious injuries in connection with the use of tetraethyl lead have occurred either in the process of manufacture of this substance or in the procedures of blending and ethylizing.”

The New York Times once again helped to spread this corporate-friendly message with a headline, “Report: No Danger in Ethyl Gasoline.”

But to actually dive into the report you would find more troubling details, echoing what Henderson had said earlier. “It remains possible that if the use of leaded gasolines becomes widespread, conditions may arise very different from those studied by us which would render its use more of a hazard than would appear to be the case from this investigation. Longer experience may show that even such slight storage of lead…may lead eventually in susceptible individuals to recognizable or to chronic degenerative diseases of a less obvious character… In view of such possibilities the committee feels that the investigation begun under their direction must not be allowed to lapse…The vast increase in the number of automobiles throughout the country makes the study of all such questions a matter of real importance from the standpoint of public health, and the committee urges strongly that a suitable appropriation be requested from Congress for the continuance of these investigations under the supervision of the Surgeon General of the Public Health Service.”

With this the committee passed a resolution calling for further studies. However, no further studies were conducted. The Surgeon General never asked Congress for more money. For the next forty years all research was exclusively conducted by the industry. And TEL production began once again.

The Surgeon General would continue to act in favorable ways to the industry. “Foreshadowing years of sterling service on behalf of Ethyl, the Surgeon General, the nation’s highest-ranking medical officer, would put pen to paper again in 1928, encouraging New York City sanitary officials to lift the city’s ban on the use of TEL-laced gasoline,” writes Kitman. “In 1931 Cumming would further assist Ethyl’s overseas marketing efforts…the Surgeon General would busy himself writing letters of introduction for Ethyl officials to public health counterparts in foreign countries.”

No direct financial links were mentioned in Kitman’s writing or other sources that were looked at, but the chances are that they were there. By his actions the Surgeon General was clearly allied to the industry rather than public health.

The FTC Restrains…the Competition

In 1936, TEL dominated 90 percent of the gasoline market. Yet, Cushing Gasoline started advertising their TEL free gasoline with ads that read, “It stands on its own merits and needs no dangerous chemicals–hence you can offer it to your customers without doubt or fear.”

As a result of this, and whatever backroom deals that must surely have taken place, the Federal Trade Commission stepped in to help Ethyl continue to monopolize. They issued a restraining order to prevent competitors from criticizing leaded gasoline in their advertising.

Their order read that Ethyl gasoline, “is entirely safe to the health of motorists and the public…and is not a narcotic in its effect, a poisonous dope, or dangerous to the life or health of a customer, purchaser, user or the general public.”

The FTC’s mission is to protect consumers from misleading advertising. Yet here we see them do exactly the opposite in protecting monopoly interests.

Lead Science

The top lead industry scientist was a man named Robert Kehoe. He was appointed as the chief medical consultant of the Ethyl Corporation in 1925. He worked there until he retired in 1958. That’s 33 years of dedicated industrial science. He was also appointed as the director of the Kettering Laboratory, funded by GM, Du Pont and Ethyl.

At a Senate committee in 1966, Kehoe said, “at present, this Laboratory is the only source of new information on this subject [occupational and public health standards for lead] and its conclusions have a wide influence in this country and abroad in shaping the point of view and the activities, with respect to this question, of those who are responsible for industrial and public hygiene.”

He further told them that they “had been looking for 30 years for evidence of bad effects from leaded gasoline in the general population and had found none.”

His findings were backed by some of the top authorities like the American Public Health Association and the American Medical Association.

After the Surgeon General’s committee, zero public science was done. The leaded gasoline industry not only had a monopoly on the product, but also a complete monopoly on the science at this point, all of it running through Kehoe’s lab. And it was shoddy industry science with a pre-conceived outcome.

Kitman writes, “In fact, independent researchers later realized, Kehoe’s control patients–the ones who wouldn’t be exposed to leaded gas in his studies–were invariably already saturated with lead, which had the effect of making exposed persons’ high lead load appear less worrisome.” These uncontrolled controls would be a mainstay of industry science. It’s a great way to show that whatever you’re looking at has no impact.

Other industry-funded associations would help to propagate such industry-friendly research. These groups included the Lead Industries Association and the International Lead Zinc Research Organization.

Leveraged Buyout

TEL’s patents expired in 1947. Yet the profits were large enough to be spread by all the top players in the industry.

In 1963, the Ethyl corporation’s annual report stated, “today, lead alkyl antiknock compounds are used in more than 98 percent of all gasoline sold in the United States and in billions of gallons more sold in the rest of the world. Leaded gasoline is available at 200,000 service stations in this country and thousands of others around the globe.”

Yet GM had decided to get out of the leaded gasoline business. This may have been due to antitrust issues that were being looked at. More likely this had to do with much debated at the time air pollution regulation that they saw coming.

Kitman writes, “American auto makers saw the threat that air pollution posed to their business. In the mid-fifties they’d concluded a formal but secret agreement among themselves to license pollution-control technologies jointly and not publicize discoveries in the area without prior approval of all the signatories, a pre-emptive strike against those who would pressure them to install costly emissions controls.”

So in 1962, GM and Standard Oil sold off Ethyl Gasoline Corporation, their leaded gasoline subsidiary, to Albemarle Paper.

After that they turned against their former product that had made them rich. A biographer for GM would write, “Here was General Motors, which had fathered the additive, calling for its demise! And it struck some people as incongruous–not to use a harsher word–for General Motors to sell half of what was essentially a lead additive firm for many millions and then to advocate annihilation of the lead antiknock business.”

In 1969, the Justice Department accused the four major auto companies, including GM, their trade association, and seven other manufacturers of conspiracy for the above-mentioned secret agreement. There’s that conspiracy word again. This suit was settled that September.

Anti-Lead Science Strengthened and the Ensuing Bribes, Threats and Actions

Meanwhile, the science regarding the dangers of lead was growing ever stronger.

Dr. Clair Patterson, a California Institute of Technology geochemist, had worked on the Manhattan Project and was widely credited with estimating the earth’s age of 4.55 billion years. He was considered a scientist beyond reproach.

In 1965 he published, “Contaminated and Natural Lead Environments of Man,” in the Archives of Environmental Health. This detailed how industry had raised lead levels 100 times in the earth and 1000 times in the atmosphere.” While lead was natural, it’s widespread dispersal had been caused by man.

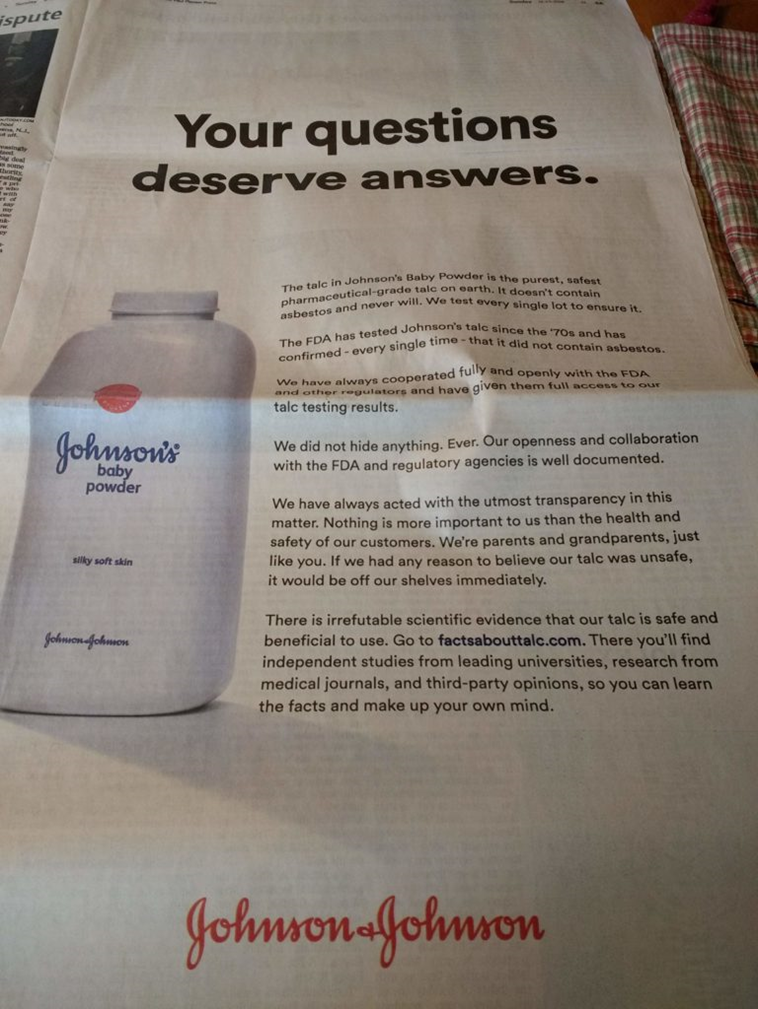

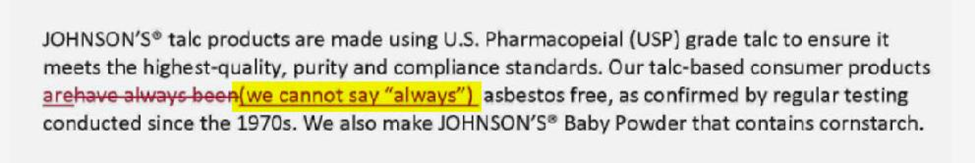

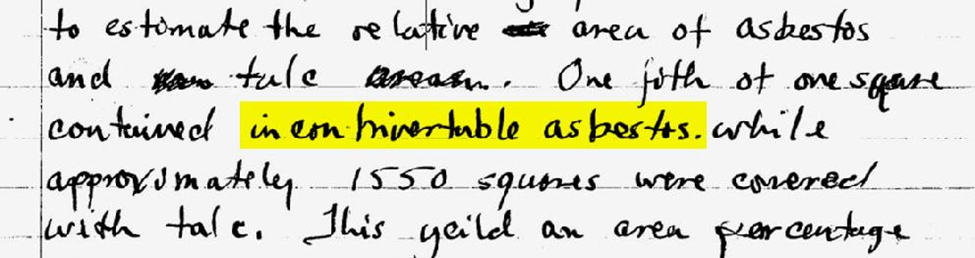

Patterson said, “It is not just a mistake for public health agencies to cooperate and collaborate with industries in investigating and deciding whether public health is endangered–it is a direct abrogation and violation of the duties and responsibilities of those public health organizations.”

Ethyl sent representatives who according to Patterson, tried to “buy me out through research support that would yield results favorable to their cause.”

The pushback is always multi-pronged. His longstanding contract with the Public Health Service was not renewed. The American Petroleum Institute also failed to renew a contract Patterson had with them.

Kitman writes, “Members of the board of trustees at Cal Tech leaned on the chairman of his department to fire him. Others have alleged that Ethyl offered to endow a chair at Cal Tech if Patterson was sent packing.”

Phasing Out Lead in Gasoline in the USA

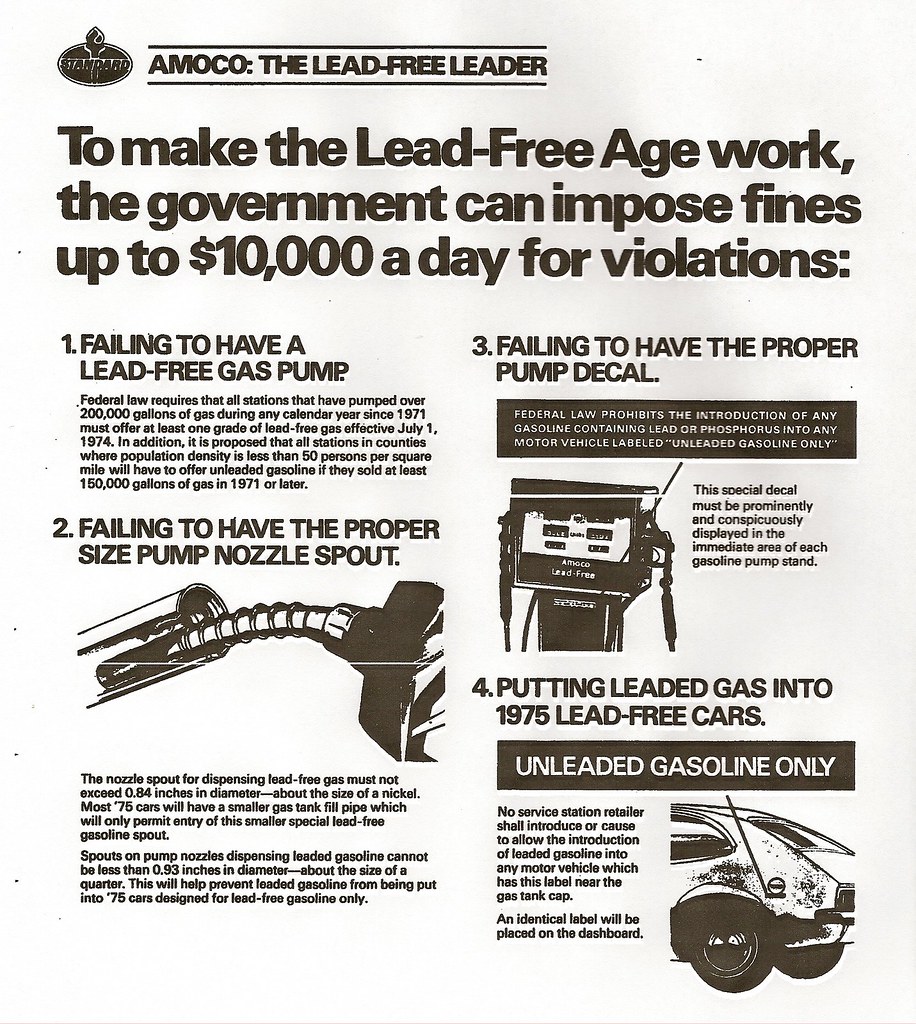

Interestingly enough, it wasn’t the health issues that caused it to go away, but tailpipe emissions. The Clean Air Act of 1970 led to catalytic converters being required for strict emission regulations. Lead damaged catalytic converters.

Within the USA, the EPA acted in 1973 to phase out leaded gasoline. New vehicles were designed to run on unleaded gasoline.

When this was announced the EPA was sued by Ethyl and Du Pont, that they were deprived of their property rights. The US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia said that the EPA’s lead regulations were “arbitrary and capricious.”

Up the chain of courts it went. In 1976, this decision was overturned because of the “significant risk” involved. Ethyl, Du Pont, Nalco and PPG, as well as the National Petroleum Refiners Association and four oil companies appealed to the Supreme Court but they refused to hear it. (Interestingly enough, Supreme Court Justice Lewis Powell had been an Ethyl director.)

An intensive lobbying campaign was launched to delay the lead phaseout. This was led by Du Pont, Monsanto and Dow.

With all of this industry-led pushback, as with most regulation when it occurs, it was a slow-moving plan.

California led the way banning leaded gas in 1992. Leaded gasoline wasn’t fully banned within the USA until 1996 for passenger cars.

Increasing Lead Worldwide

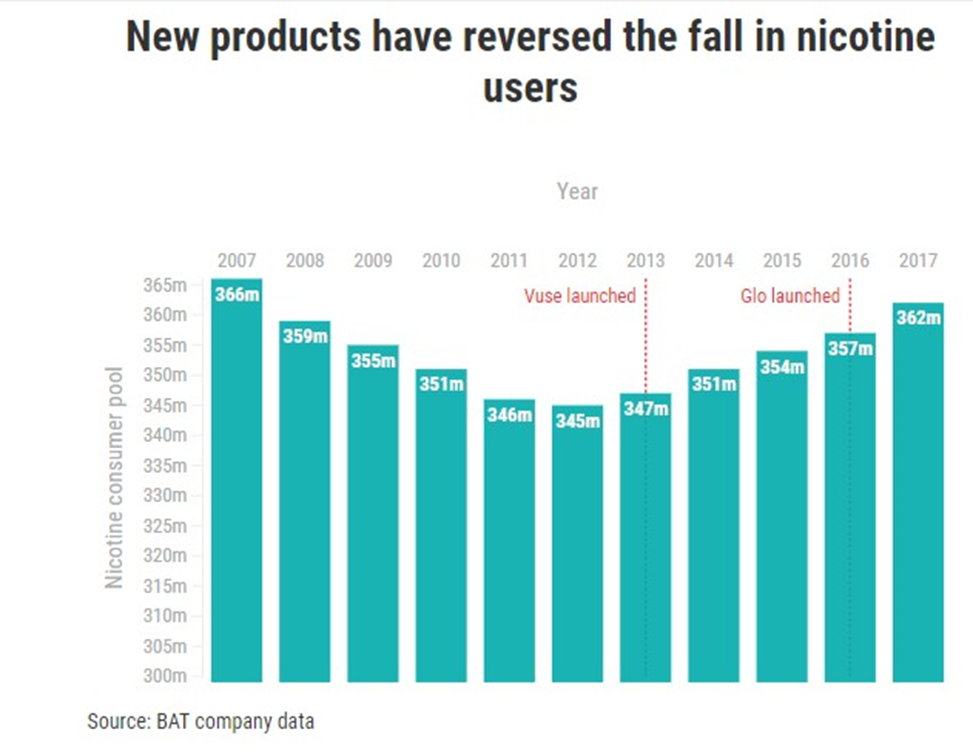

By 1979 Ethyl found, “It is worth noting that during the second half of 1979, for the first time, Ethyl’s foreign sales of lead antiknock compounds exceeded domestic sales.” With increasing regulation in the USA, the strategy of going worldwide would become more prevalent.

When the USA had finally banned leaded gasoline in all passenger cars in 1996, other countries were far behind. The percentage of leaded gasoline sold included:

- 93% Africa

- 94% Middle East

- 30% Asia

- 35% Latin America

Not only that, but additional steps would be taken to ensure that profits remained high. In other countries the industry would help to get even more lead added to gasoline. This was of no benefit except to their bottom line. India more than doubled how much lead was in its gasoline, from 0.22 to 0.56 grams per liter.

Another big leaded gasoline company was Octel. They reported in a 1998 SEC filing, “From 1989 to 1995, the Company was able to substantially offset the financial effects of the declining demand for TEL through higher TEL pricing. The magnitude of these price increases reflected the cost effectiveness of TEL as an octane enhancer as well as the high cost of converting refineries to produce higher octane grades of fuel.”

Certain imports and exports only made sense in light of profit motives. “Ironically, in the nineties the Venezuelan state oil company, Petroleos de Venezuela, exported unleaded gasoline. But it was importing TEL and adding it to all gasoline sold for domestic use,” reports Kitman. “By way of explanation, it is perhaps not unhelpful to know that several high-ranking officials of the state oil company held consultancies with companies that sell lead additives to the country.”

Phasing Out Lead Worldwide

In 2002, the United Nations Environment Programme launched an effort to stop worldwide use of leaded gasoline. Most countries started on this immediately, but some countries did not. This included Algeria, Afghanistan, Iraq, Yemen, Myanmar, and North Korea.

Rob de Jong, the head of UNEP’s sustainable transport unit, said “In some of these countries, officials were bribed by the chemical industry that was producing these additives…They were bribed to buy large stockpiles.”

Finally, in 2021 lead in gasoline was banned and phased out completely for passenger vehicles across the world. Algeria was the final country to stop using it.

However, while leaded gasoline is no longer used worldwide for passenger cars, it is still used for other vehicles, including some aircraft, motorsports, farm equipment, marine engines and off-road vehicles. This includes in the USA.

Diversification

Despite the problems, Ethyl continued to thrive. By 1983 they had become the world’s largest producer of organo-metallic chemicals. In addition to expansion into the petroleum industry, they would expand into specialty chemicals, plastics, aluminum, oil, gas, coal, pharmaceuticals, biotech research, semiconductors and life insurance.

Ethyl’s 1996 annual report shared their “long-running strategy: namely, using Ethyl’s significant cash flow from lead antiknocks to build a self-supporting major business and earnings stream in the petroleum additives industry.”

Ethyl Corporation, as a subsidiary of NewMarket Corporation, is still going strong. They’re making total revenues of over $2 billion per year.

Erik Millstone of the Science and Technology Policy Research Unit at Sussex University reviewed all the scientific evidence on lead exposure in 1997. He found that children where four to five times as susceptible to the effects of lead as adults.

The good news is that lead levels fell rapidly when leaded gasoline was no longer used.

Still, these dangerous effects wouldn’t be completely eliminated. A 1992 article in The New England Journal of Medicine compared pre-Columbian inhabitants of North America to those living in the present day. The authors found that the average blood-lead levels were 625 times lower earlier in history.

Rabinowitz in an article for Environmental Health Perspectives, states “Bone lead levels generally increase with age at rates dependent on the skeletal site and lead exposure. The slow decline in blood lead, a 5- to 19-year half-life, reflects the long skeletal half-life.”

What this means is that because of leaded gasoline in the past, you and I still have lead in our bones. The sins of the fathers…

Key Takeaways on The Leaded Gasoline Industry

- Lead was used in gasoline for its antiknock effects. It was already known to be poisonous at the time, and there already were better alternatives, especially ethanol. But it had a fatal flaw for the industry, it wasn’t patentable.

- Leaded gasoline would aerolize lead getting it in the air, soil and water. Their pollution affected every single man, woman and child the world over causing cancer, neurodegeneration, cardiovascular problems and more. It is especially dangerous to developing children. No one was immune.

- The companies behind these actions were General Motors, Du Pont, and the various Standard Oil spin offs (nowadays ExxonMobil).

- The man who invented tertraethyl lead’s use in gasoline himself suffered from lead poisoning. To prove its safety, he would literally rub it into his skin at exhibitions. He had previously patented an ethanol gasoline method but this wasn’t as profitable so GM never used it and would later claim there were no alternatives.

- The US Surgeon General Hugh S. Cumming was effectively in the pocket of the industry. He helped to cover up deaths from lead poisoning, expanding the reach of the industry to the worldwide market, and doing no further research on the risks of lead gasoline. With no research the industry could claim there was no research to show it had risks.

- There were other friends in high places. The FTC put a restraining order on competitors saying leaded gasoline “is entirely safe to the health of motorists and the public.” No competitors could bring up the health dangers.

- The New York Times, for one reason or another provided cover for the industry including the front-page headline: “Report: No Danger in Ethyl Gasoline,” even though the report discussed the need for more research and longer term potential issues.

- Robert Kehoe was the chief medical consultant of the Ethyl Corporation (formed by GM and Standard Oil). In front of Congress in 1966 he said that he “had been looking for 30 years for evidence of bad effects from leaded gasoline in the general population and had found none.” In his research his control patients already had lead exposure thus leading to the outcomes desired by the industry.

- Dr. Clair Patterson, a California Institute of Technology geochemist, onetime member of the Manhattan Project published in 1965 “Contaminated and Natural Lead Environments of Man.” This found how industry had raised his lead burden 100 times and levels of atmospheric lead 1,000 times. The industry attempted to buy him out, had other scientific contracts canceled and tried to get him fired.

- Many countries began banning leaded gasoline. The USA started in the 1980’s. The last country in the world, Algeria, finally did so in 2021.

- However, leaded gasoline is only banned in passenger cars. Leaded gasoline is still used in some aircraft, motorsports, farm equipment, marine engines and off-road vehicles including in the USA.

Please leave any comments or questions below. Feel free to share it with anyone you’d like.

Links to all published chapters of The Industry Playbook can be found here.

You can also support this project with a tip.