This is Chapter 17 of my new book, working title “The Industry Playbook: Corporate Cartels, Corruption and Crimes Against Humanity” that is being published online chapter by chapter.

Legal bribes in the form of political contributions were mentioned in an earlier chapter. That is one form of it. For scientists. it can come in the way of grants. For regulators and lobbyists in the form of employment. And for pretty much anyone, it can come in the form of consultancy deals. That can all be legally done, thus making up a significant part of the industry playbook.

But legal bribes are just one part of it. We can see examples of illegal bribes too. Certainly, with everything we’ve seen Big Tobacco do, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that this is a utilized strategy.

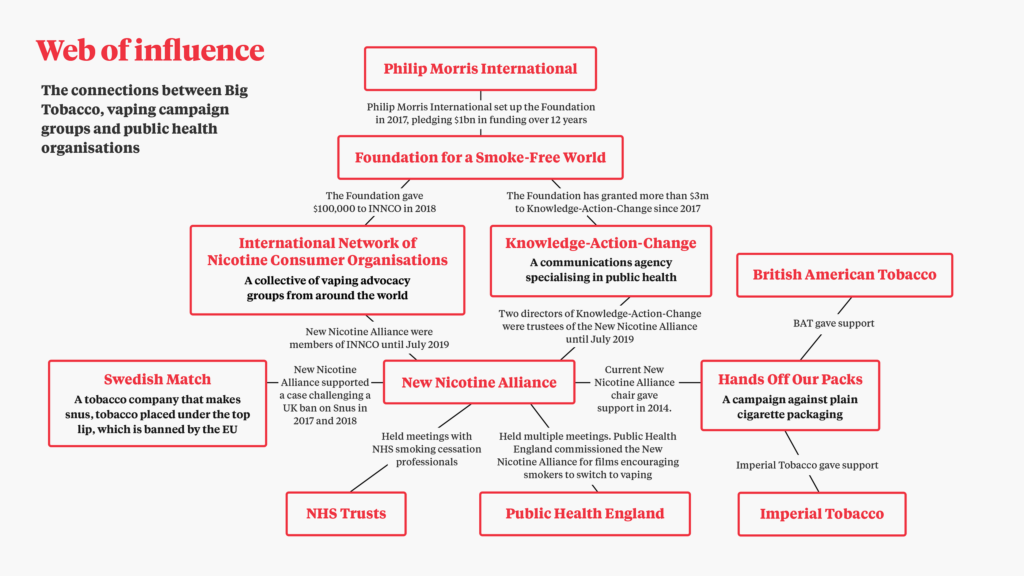

Brandt doesn’t cover this subject much beyond the rumors of the early 20th century Tobacco Trust bribing state legislators. So for this chapter we turn to 21st century examples, most of which are done by British American Tobacco (BAT).

“BAT is bribing people, and I’m facilitating it,” said whistleblower Paul Hopkins, who leaked internal documents. “The reality is if…they have to break the rules, they will break the rules.” Hopkins worked for BAT in Kenya for 13 years.

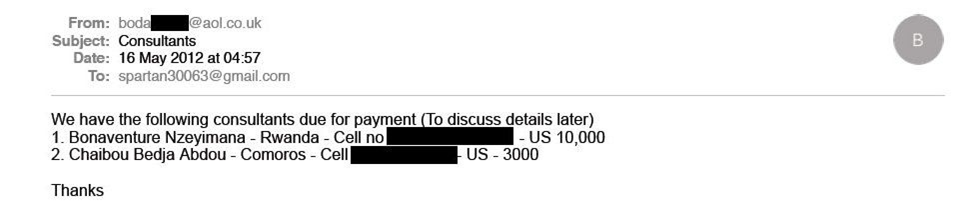

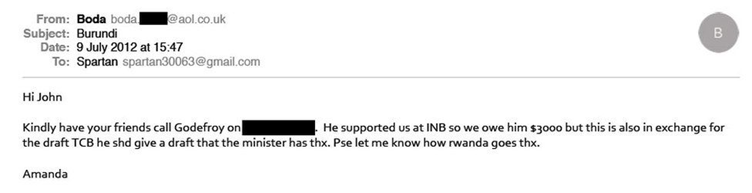

Emails revealed by Hopkins shows that they made payments to members of the WHO’s FCTC, undoubtedly for assistance in undermine the health treaty.

In an article from the BBC they write, “[A]n email from a contractor working for BAT says Mr Kamwenubusa would be able to ‘accommodate any amendments before the president signs’.” That means that the bribe was effectively buying specific wording on policy.

Of course, BAT categorically denies such actions, stating “The truth is that we do not and will not tolerate corruption, no matter where it takes place.” But when you dig deeper BAT even described some payments to three public officials in Rwanda, Burundi and the Comoros Islands as “unlawful bribes” in one document.

The INB is the FCTC’s Intergovernmental Negotiating Body. The TCB is the Tobacco Control Bill. This bribe was for supporting them at the meeting as well as providing the draft of the document.

The BBC lists additional cases. “Former BAT lobbyist Solomon Muyita was fired by BAT in Uganda in 2013 after he was accused of giving cash gifts to 50 people, including seven MPs. He says he was following company orders and is suing BAT for wrongful dismissal. The company says Muyita is lying.”

BAT funded a South African private security company called Forensic Security Services (FSS). They were officially tasked with fighting the black-market cigarette trade. But that is not all they did. Internal documents showed how their staff were instructed to close down three cigarette companies owned by BAT’s competitors. Bribes were dispersed in covering up when illegal surveillance was caught.

“I had to make it clear that they’re going to expect a nice thick envelope of notes,” a whistleblower said. “I would be given a lump sum of money as an operational budget and out of that I would always give a handshake and a nice wodge of cash to the principals just to warm them to the idea.”

This went all the way up to Robert Mugabe, the brutal dictator of Zimbabwe. Documents show that his Zanu-PF party was possibly paid between $300,000 and $500,000 by BAT in 2014.

These documents made their way to the Serious Fraud Office of the UK government where the case was investigated. On January 15th, 2021 they found that the “evidence in this case did not meet the evidential test for prosecution.”

This is pure conjecture, but is it possible additional bribes were paid to help make that go away?

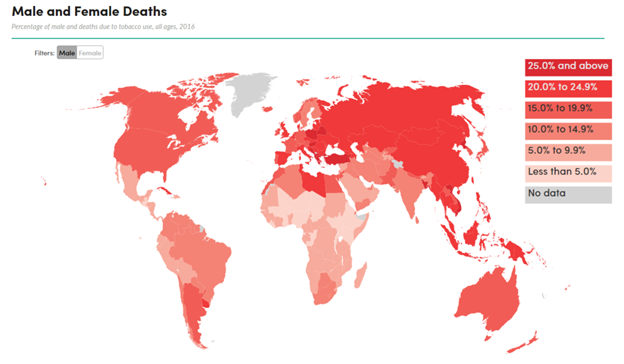

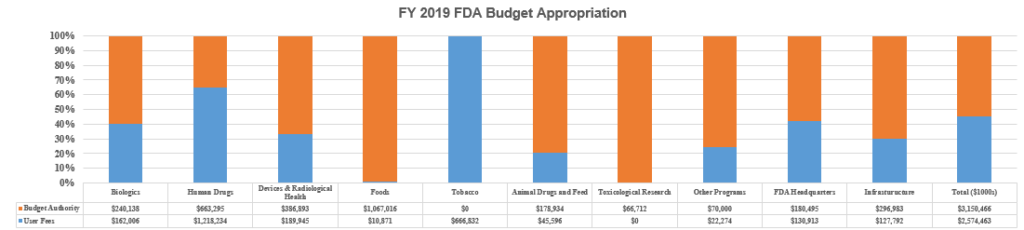

As corruption is stronger in many countries than the USA, we see this as an added benefit of going worldwide. “These large tobacco merchants used secret payments to improperly win business and curry favor with foreign government officials around the globe,” said Christopher Conte, Associate Director in the SEC’s Division of Enforcement.

The SEC went after two companies. Universal paid $800,000 in bribes to officials of the government-owned Thailand Tobacco Monopoly for securing approximately $11.5 million in sales contracts for its subsidiaries. Alliance One paid $1.2 million for $18.3 in sales contracts.

That was in Thailand. The SEC also alleged bribery in China, Greece, Indonesia, Kyrgyzstan, Malawi and Mazambique.

These bribes don’t just go to politicians. In an even more recent case journalists were similarly influenced or at least attempted to.

Edwin Okoth was working with The Bureau of Investigative Journalism, looking into Kenya’s advertising described in the following chapter. A Kenyan PR agency, Engage BCW, was working for BAT. Here is a text message between Okoth and an employee from Engage.

Engage BCW said that this is against their rules, that their employees undergo anti-bribery training and the employee was suspended.

“Offering a bribe to a journalist isn’t just an attempt to undermine honest reporting and journalistic integrity, the very offer of a bribe is a crime in most jurisdictions,” said Rory Donaldson, programme manager at Transparency International, an anti-corruption charity organization. “Corporations should be aware of the activities of third parties acting on their behalf such as PR agencies. When undertaking internal investigations corporations must ensure the investigation is not a whitewash. Bringing in external investigators can help mitigate this risk.”

These are just a few examples of what has been caught. Imagine all the bribes that they have gotten away with over the years.

Key Takeaways on Bribery

- There are illegal bribes and legal bribes. Both make their way into the industry playbook.

- Bribery works well with the tactic of going worldwide, where in many places corruption is more rampant, and thus bribery is easier to do and get away with.

- Internal documents reveal how British American Tobacco was able to influence politicians drafting the WHO’s treaty on tobacco control.

- Whistleblowers reveal examples and documentation of bribery, while the companies deny any such claims always stating how ethical they are despite the evidence.

- Examples show not just politicians and law enforcement, but also journalists too. Any professional worth influencing is capable of being targeted.

Please leave any comments or questions below. Feel free to share it with anyone you’d like.

Links to all published chapters of The Industry Playbook can be found here.

You can also support this project with a tip.