This is Chapter 7 of my new book, working title “The Industry Playbook: Corporate Cartels, Corruption and Crimes Against Humanity” that is being published online chapter by chapter.

One of the key strategies is to propagate information that suits your agenda while making it appear to come from independent and authoritative sources. That is what front groups are for. It is a tried-and-true PR method, which is why you must always follow the money.

To properly show this power imagine an organization says that tobacco doesn’t cause disease.

- If the tobacco companies said it themselves, you would see it as self-serving immediately.

- If there was a standalone organization you might consider the message, even if it was funded by Big Tobacco, because you might not know how deep the conflicts go.

- If that organization was truly independent, then you would rightfully consider the message.

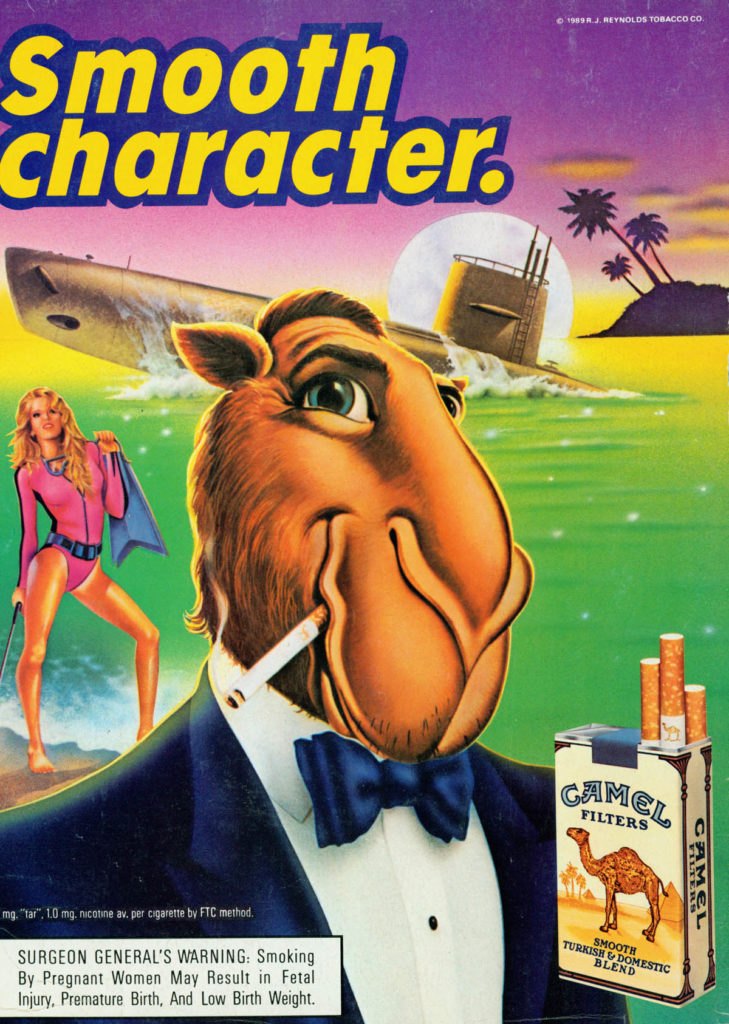

The tricky part is that the funding is very often obfuscated. And it can quickly become complicated to hide such connections. The PR effort is always to appear truly independent, especially today. But remember, Big Tobacco were pioneers in this method. Early on it was quite a bit more direct.

In November of 1953 R.J. Reynolds formed a “Bureau of Scientific Information” to “combat the propaganda which is being directed at the tobacco industry.” Two months later, the industry announced the creation of the Tobacco Industry Research Committee (TIRC). Hill & Knowlton recognized that a joint effort would work better.

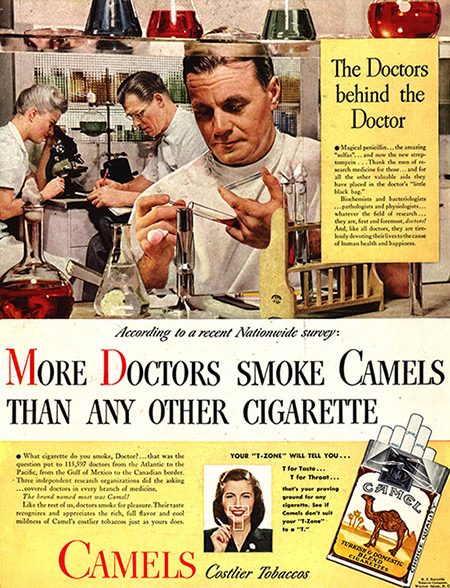

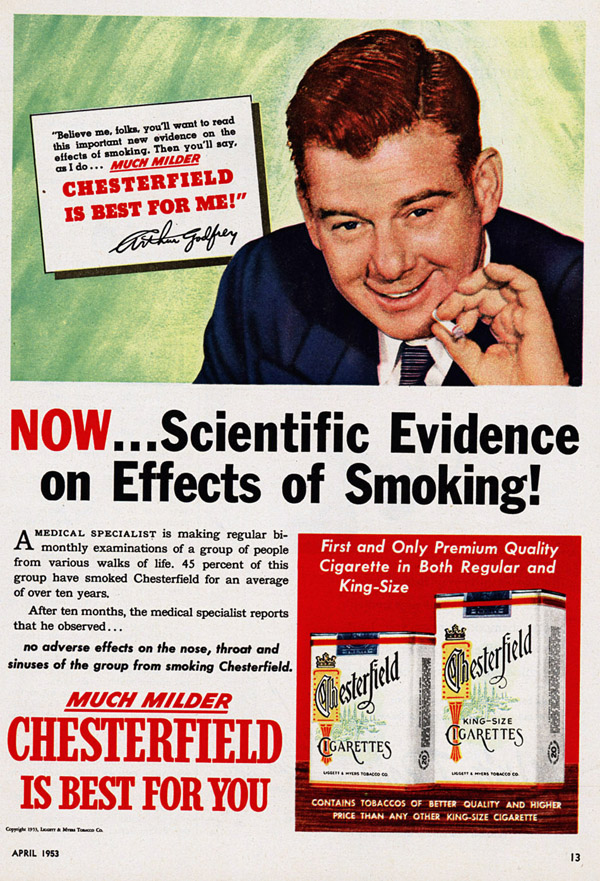

Notice the names of these organizations. Bureau of Scientific Information. Tobacco Industry Research Committee. Science was really coming into its own around this time. These organizations used the authority of science within the names of the organization. This was a way of seizing credibility just from the name itself.

Imagine if one of these organizations had been named the Tobacco Industry Propaganda Committee. This would be more accurate to what they did, which is exactly why it would never be named as such.

Science is just one of the areas where a group can advocate for. In 1964 the TIRC changed its name to the Council for Tobacco Research (CTR). And in 1966 CTR had a Special Projects program. This included establishing “expert scientific witnesses who will testify on behalf of the industry in legislative halls, in litigations, at scientific meetings, and before the press and public.” In other words, those front groups require front people.

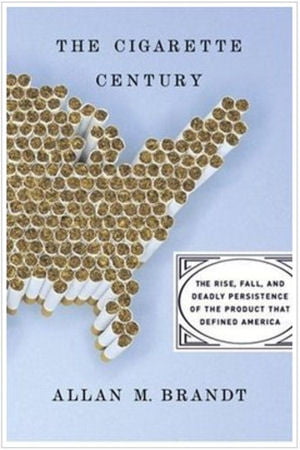

These advocacy front groups can be used in a multitude of ways. For instance, “Philip Morris helped fund the National Smokers’ Alliance (NSA), a ‘grassroots’ organization created with the assistance of the PR firm Burson-Marsteller (BM) to advocate smokers’ rights and oppose smoking restrictions,” writes Brandt. “Claiming some three million members, NSA sought to promote a pro-smoking agenda ‘unlinked’ to the industry. But it soon became clear that the NSA was a front for industry interests.”

BM ran newspapers ads to recruit members. They setup a toll-free number. They paid telemarketers and canvassers. And they published a member’s newsletter. In 1995 the NSA claimed a membership of 3 million people. However, less than 1% of it’s funding came from members. The rest came from BM via Big Tobacco. In fact, the NSA was headed up by a vice president of BM.

This is what is known as astroturf, as in fake grassroots. The power of a grassroots organization, where there are real people that are passionate about something and try to change legislation and the like can sometimes make real change. For instance, in 1973, campaigning by real grassroots organization Arizonans Concerned About Smoking, founded by Betty Carnes, led to Arizona being the first state within the USA to pass a law restricting smoking in public places.

Recognizing this, Big Tobacco and others have weaponized the idea of grassroots by building and funding front groups of this nature.

Campaigns & Elections magazine described astroturf as “grassroots program that involves the instant manufacturing of public support for a point of view in which either uninformed activists are recruited or means of deception are used to recruit them.”

“The whole point of astroturf is to try to give the impression there’s widespread support for or against an agenda when there’s not. Astroturf seeks to manipulate you into changing your opinion by making you feel as if you’re an outlier when you’re not,” says award winning investigative journalist Sharyl Attkisson.

The key to good astroturf is to make it appear independent and real. In fact, PR agencies will talk about real grassroots, when all they mean by that is astroturf that appears real. Sometimes they rope people in through the weaponization of values discussed earlier.

In 1988, the tobacco companies were up against a new threat, secondhand smoke. So, they formed the Center for Indoor Air Research (CIAR) to deflect blame from secondhand smoke onto other indoor air pollutants. A memo mentions this strategy:

- Mobilize all scientific studies of indoor air quality (i.e., radon, wood stoves, gas stoves, formaldehyde, asbestos, etc.) into a general indictment of the air we breathe indoors. Use a scientific front—especially some liberal Nader group.

- Use this material to fuel PR offensive on poor indoor air quality.

When they talk specifically about “scientific fronts” you can be sure it’s about advancing an agenda, not actually doing real science. Reflect on how this amounts to pollution of the scientific commons.

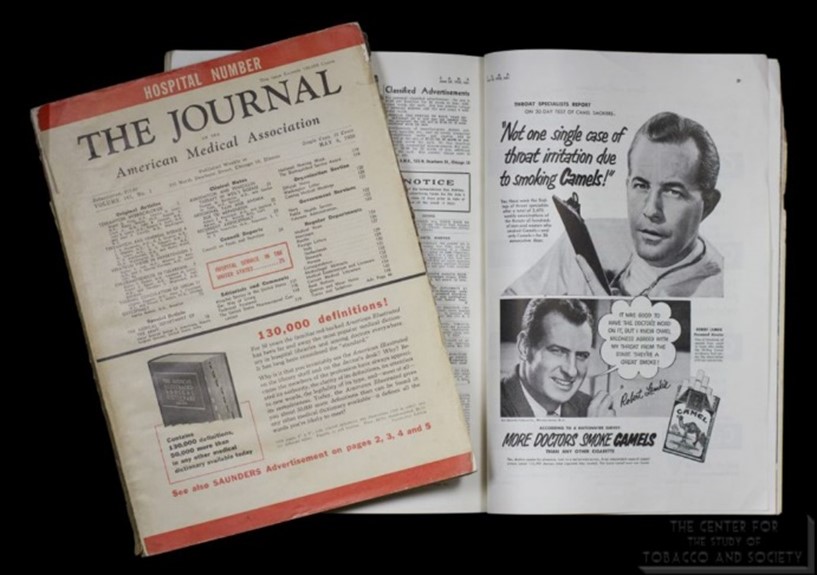

Brandt writes, “In a review of more than one hundred scientific review articles about ETS [environmental tobacco smoke] that appeared between 1980 and 1995, researchers found that 37 percent concluded that ETS was not a risk to human health. Three-quarters of these articles were authored by scientists with ties to the tobacco industry, many through CIAR.”

You may not be able to completely control the scientific conversation, but you definitely can influence it and muddy the waters.

Philip Morris, along with PR Firm APCO Associations, established a “sound science” coalition aimed at improving science by rooting out “junk science”. This included aims to revise the standards of scientific proof, so that harms of secondhand smoke were impossible to prove as causative. They initiated a campaign, “Good Epidemiological Practices.” An internal memo said this was “to impede adverse legislation.”

Notice that they tried to influence how science itself was conducted to benefit themselves.

Also note these words. Sound science. Junk science. These are nothing more than PR labels that are thrown about in order to control what paid attention to and what should not. This goes back to smear campaigns. In this case they smear the science itself in addition to the person. Sadly, these labels do work on many.

If a scientist, “skeptic”, or politician is saying we have sound science here and any other science that says the opposite is junk, you might just flip that around. Invert it because it is often a case of projection.

These are just some of the front groups established by Big Tobacco to control the messaging. And forming new groups is only part of the strategy. The other part involves the influence of those organizations that already exist, which we turn to next.

Key Takeaways on Advocacy Front Groups

- Just like you shouldn’t judge a book by its cover, you shouldn’t judge an organization by its name. First and foremost, the names of such front groups are created to look and sound credible to assist in PR efforts.

- An astroturf organization is one that is specifically meant to look like it is grassroots, meaning that the public started it and is being active in its efforts to cause change. But setting up astroturf is something that PR firms specialize in because the method works.

- The power of such front groups comes from them looking like independent and grassroots efforts, while having the bankrolling of industry. Compare this to real grassroots that typically are bootstrapped and funding only by donations.

- Front groups require front people. These people are utilized in the media, in courts, in politics, in science and anywhere they can be useful, with the support of the groups behind them.

- Front groups are used to hire scientists and promote science that is helpful to the industry’s agenda. Sadly, the phrases “sound science” and “junk science” are nothing more than PR labels thrown around to lend credibility to industry science and smear any opposition.

- When looking at any group you need to look at the funding of it. Sometimes it is hidden away and you can’t even find details. Sometimes it is mostly upfront. Still more times it is hidden in a web of multiple front groups to obfuscate where the money starts from.

Please leave any comments or questions below. Feel free to share it with anyone you’d like.

Links to all published chapters of The Industry Playbook can be found here.

You can also support this project with a tip.