This is Chapter 5 of my new book, working title “The Industry Playbook: Corporate Cartels, Corruption and Crimes Against Humanity” that is being published online chapter by chapter.

Science has basically become a religion in the modern age. In many ways science has come to replace any form of deity as the arbiter of truth. Getting into all the implications, for good or ill, of what this means is beyond the scope of this chapter. Rather I point this out to show that “religious belief” in science itself exists.

This area is subject to fundamentalism as much as religions themselves. What’s worse is that scientists and skeptics tend to be even more blind than religious zealots due to thinking that they are completely rational, and therefore above and beyond such things.

Science needs to be debatable. What we’re seeing right now is more censorship of what real scientific debate should be. And that is largely because corporate controls of science have become even stronger than back in Big Tobacco’s day.

There absolutely was a time when the harms of smoking tobacco were not known scientifically. But the fact that Big Tobacco could weaponize natural and healthy scientific skepticism, twisting it into constant denial while knowing the truth of the matter is a big problem.

Conducting high quality science is difficult enough without the profit motive intervening! But when we add that to the mix, well, that is how we arrive where we are today.

Brandt writes “The tobacco industry’s PR campaign permanently changed both science and public culture.” Think about that for a minute. The culture at large. Science at large. Recognize the impacts were not just regarding tobacco but setting precedent for every other big industry. Anyone with the money and power to do so could similarly seek to control scientific opinion. And so they did.

The aim of this chapter is two-fold. First is to give you a clear idea of the science that was coming out that showed the harms of tobacco smoke and how early this occurred. Secondly, is to show that the tobacco companies recognized these truths but fought against it tooth and nail. This is clearly shown from their own private internal research juxtaposed with their public positions.

This may read like a laundry list of science, but I feel it is necessary to give you enough of an overview of how the science developed and was influenced.

There were signs of the dangers of tobacco smoke scientifically as early as 1928 when a New England Journal of Medicine study found a 27% increase of overall cancer rates among heavy smokers.

In 1930, an Argentinian scientist, Ángel Roffo, found polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, known carcinogens, in tobacco tar.

Dr. James J. Walsh summarized the current medical opinion in 1937 that once rare diseases were becoming fairly common.

Then in 1938, Raymond Pearl, an eminent John Hopkins biologist, found, “the smoking of tobacco was statistically associated with the impairment of life duration, and the amount of this impairment increased as the habitual amount of smoking increased.” This was the first science showing dose-dependent detrimental health effects.

In 1940, scientists found tobacco smoke exposure lowered birth weight and hindered growth and development in pregnant rats.

None of these studies conclusively “proved” tobacco smoke was harmful. But the case was being built.

In 1950, the science really started to solidify. In May of that year, JAMA published a paper by Wynder and Graham, “Tobacco Smoking as a Possible Etiologic Factor in Bronchiogenic Carcinoma: A Study of 684 Proved Cases.” Then in September, Doll and Hill published in the BMJ, “Smoking and Carcinoma of the Lung: Preliminary Report,” the first ever retrospective study. They calculated a statistical significance of 0.00000064 that smoking caused lung cancer, that is their findings had less than one in a million chance of being random.

Brandt writes, “[M]odern epidemiology was constructed around the problem of determining the harms of smoking…As more studies accrued, so too did medical and public confidence in the conclusion. This aggregative process marked a significant difference in scientific epistemology from the traditional notions of individual investigators ‘making’ scientific ‘discoveries.’ In epidemiology, discovery and proof were iterative, as no specific experimental situation could be precisely replicated. Researchers now sought to take advantage of this variability; ‘consistency’ across multiple studies would become another criterion for defining causality.”

In February 1953, a R.J. Reynolds scientist, Claude Teague, wrote in an internal memo, “Studies of clinical data tend to confirm the relationship between heavy and prolonged tobacco smoking and incidence of cancer of the lung.” Later that year, in December, Wynder, Graham and Croninger published mouse experiments in Cancer Research giving strong biological plausibility for smoking causing cancer.

This is when Big Tobacco came together to mount a defense. They formed the Tobacco Industry Research Committee (TIRC). As previously mentioned they released a paper titled A Scientific Perspective on the Cigarette Controversy. The thing is this paper didn’t actually contain any new science, instead being just eighteen pages of quotes from doctors and scientists doubting the link.

Part of the TIRC was the Scientific Advisory Board (SAB). Clarence Cook Little was elected to its chair. He was a eugenicist who believed cancer was exclusively hereditary. In other words, he had an ideological position that cigarettes couldn’t be the cause. To him cigarettes were innocent and could never be proven guilty. Therefore, he was the perfect scientific front man for Big Tobacco.

In November of 1954, the first grants from the TIRC went out to scientists. These mostly focused on trying to find how cancer was linked to anything besides tobacco smoke.

The TIRC pointed their scientific lens where it would benefit them. Cancer was looked at via genetics or other environmental risks. No statistical or epidemiological science was done. Almost no direct research looked at cigarettes.

In 1970, Helmut Wakeham, director of R&D at Philip Morris, would explain it as such, “Let’s face it. We are interested in evidence which we believe denies the allegation that cigarette smoking causes disease.”

With cigarettes and cancer, it wasn’t easy to see a cause-and-effect relationship. You don’t smoke a single cigarette and get cancer. Instead, the science became solidified over time because of clinical observations, population studies and laboratory experiments. All of these were different layers of evidence. Yet, Big Tobacco dismissed it all as mere statistics. They smeared the science itself.

Still more scientific evidence continued to mount. In 1956, Doll and Hill published “Lung Cancer and Other Causes of Death in Relation to Smoking: A Second Report on the Mortality of British Doctors.” This found smokers had death rates 24 times higher than nonsmokers.

In 1957, pathologist Oscar Auerbach published research in the NEJM looking at precancerous changes to lung tissue in autopsies of 30,000 deceased patients with smoking histories.

That same year, scientists from American Cancer Society, American Heart Association, National Cancer Institute, and the National Heart Institute looked at the data and concluded: “The sum total of scientific evidence establishes beyond reasonable doubt that cigarette smoking is a causative factor in the rapidly increasing incidence of human epidermoid carcinoma of the lung…The evidence of a cause-effect relationship is adequate for considering the initiation of public health measures.”

To this, Dr. Little responded, “The Scientific Advisory Board questions the existence of sufficient definitive evidence to establish a simple cause-and-effect explanation of the complex problem of lung cancer.” This is no explanation instead just explaining the evidence away.

Big Tobacco continued to fight against the science. That same year, internal documents at British American Tobacco referred to cancer only in code words. “Tobacco smoke contains a substance or substances which may cause ZEPHYR.” They didn’t even dare use its name internally for fear of the documents getting out as they eventually did.

In 1958, members from the Tobacco Manufacturers Standing Committee, the British counterpart to the TIRC, visited the US to look at industry-related science. They wrote, “The majority of individuals whom we met accepted that beyond all reasonable doubt cigarette smoke most probably acts as a direct though very weak carcinogen on the human lung. The opinion was given that in view of its chemical composition it would indeed be surprising if cigarette smoke were not carcinogenic. This undoubtedly represents the majority but by no means the unanimous opinion of scientists in the U.S.A.” That same year, the TIRC drafted “Another Frank Statement to Smokers.” Despite the internal scientific conclusions, the PR firm wrote “The cause of cancer remains as much a mystery as ever.”

The PR campaign worked wonderfully. By 1960, the “scientific controversy” about tobacco causing cancer was widely debated in the media and by the public.

Again, all we have to do is compare what they were talking about internally with their external messaging. For example, in 1961, Philip Morris director of research and development, Helmut Wakeham listed 15 carcinogens and 24 “tumor promoters” in cigarette smoke. He also found, of the more than 400 compounds in cigarette smoke, 84% of them are present in secondhand smoke. Meanwhile TIRC was putting out statements saying, “Chemical tests have not found any substance in tobacco smoke known to cause human cancer.”

In 1963, James C. Bowling, vice president and director of Philip Morris, said “We believe there is no connection or we wouldn’t be in the business.”

In 1964, the Surgeon General’s report was released stating, “No reasonable person should dispute that cigarette smoking is a serious health hazard.” This was after two years of investigation from a committee under Surgeon General Luther Terry.

“Without these efforts [to control the scientific narrative], the harms of smoking would have been uniformly accepted by medical science long before the 1964 surgeon general’s report,” Brandt writes. “Given the definitive findings of the surgeon general’s report, the cigarette companies were forced to redouble their efforts to maintain the smoke screen of ‘scientific controversy’ and ‘uncertainty.’ They quickly developed a policy, developed by their legal staffs, to neither deny nor confirm the findings. In public, they continued to insist on the need for more research; the ‘merely statistical’ nature of the surgeon general’s conclusion.”

Fortunately, their public messaging began to get weaker in those regards. The public began to see through their tricks and accepted the cancer link. But the scientific and PR battlefront moved elsewhere, mostly to secondhand smoke, as well as the addictiveness of cigarettes.

Their internal researchers knew about the dangers of secondhand smoke before anyone in the public was talking about it too.

In 1967, Philip Abelson, editor of Science, implicated cigarette smoke as “a serious contributor to air pollution” which can affect not just the smoker but those nearby.

In 1981, epidemiologist Takeshi Hirayama of the Tokyo National Cancer Research Institute found that wives of smokers and ex-smokers had increased rates of lung cancer in a dose-response relationship to exposure. That same year, the National Academy of Sciences committee on indoor air pollutants directed attention to indoor cigarette smoke.

In 1983, a legal memo from a law firm working for Philip Morris quotes researchers Victor DeNoble and Paul Mele in their paper “Nicotine as a Positive Reinforcer in Rats” that “their overall results are extremely unfavorable” that “research such as this strengthens the adverse case against nicotine as an addictive drug.”

In 1986, a National Academy of Sciences report showed that children of smokers were twice as likely to suffer from respiratory infections, pneumonia, and bronchitis as children of non-smokers. This report estimated that environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) caused between 2,500 and 8,400 lung cancer deaths per year.

Big Tobacco criticized these findings and got to work. In 1988 the tobacco companies formed Center for Indoor Air Research (CIAR) a front group to deflect blame from secondhand smoke onto other indoor air pollutants.

In 1993, Philip Morris, along with PR Firm APCO Associations, established a “sound science” coalition aimed at improving science by rooting out “junk science”. This included aims to revise the standards of scientific proof, so that harms of secondhand smoke were impossible to prove as causative.

Another Surgeon General’s report, released in May 1988, focused on the addictiveness of smoking, specifically from nicotine.

In 1994, ABC’s Day One news program featured “Deep Cough” a whistleblower from R.J. Reynolds saying that tobacco companies knowingly added more nicotine to cigarettes to increase addictiveness. Yet Big Tobacco continued to deny anything negative about their product.

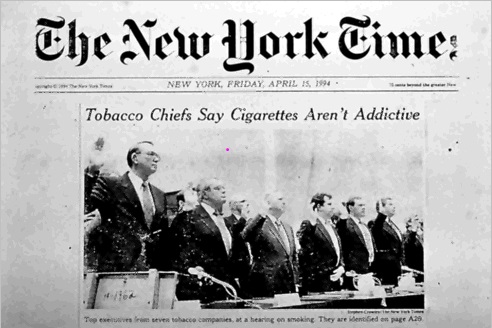

In April of 1994, chief executives of the top seven tobacco companies appeared before a Congressional subcommittee headed by Henry Waxman. They all stated that tobacco was not addictive nor that they manipulated nicotine levels in cigarettes. Lorillard CEO Andrew Tisch said, “We have looked at the data and the data that we have been able to see has all been statistical data that has not convinced me that smoking causes death.” R.J. Reynolds CEO James W. Johnston said, “Cigarette smoking is no more addictive than coffee, tea or Twinkies.”

This was not an exhaustive list of all the science that came out, nor all the efforts of tobacco to fight against it. But it should be sufficient to show that science was heavily influenced, maybe not in the minds of many of the experts themselves, but certainly in the public battlefield.

What were the results of this seeking to control of science? How many deaths are directly attributable to this manipulation of science, year after year, decade after decade?

That would be a hard number to calculate. An easier number to find is the millions upon millions in profits for the tobacco companies for acting in this way. Science clearly can be bought, if not completely, at least to a large enough degree to matter.

Key Takeaways on Influencing Science

- There absolutely was a time when the dangers of smoking weren’t knowing scientifically. But the first hints began in 1928 and the evidence was very compelling by the early 50’s.

- The full picture is grasped when you compare what Big Tobacco’s internal research documentation showed as opposed to their public opinions. With that you know the difference between science and PR.

- Internal research in the tobacco companies was often ahead of public research. For instance, Big Tobacco scientists knew about the dangers of secondhand smoke before anyone else was talking about it.

- When scientific proof of the dangers of smoking was overwhelming, Big Tobacco’s policy changed to neither confirming nor denying it, while they continued to deny the science of secondhand smoke dangers and addictiveness of nicotine.

- Tactics of influencing science involve:

- Smearing the scientists that come out with research implicating tobacco

- Smearing the science itself as merely statistical or insufficient evidence

- Not publishing any internal science you’ve conducted that would be damaging

- Doing research in areas that can’t possibly hurt your agenda, such as studying other causes of cancer

- Publishing any science that fits the agenda, then promoting it far and wide through the network of media contacts

- Influencing journalism by always insisting there are two sides

- Utilizing front groups and networks at institutions to push the agenda forward

Please leave any comments or questions below. Feel free to share it with anyone you’d like.

Links to all published chapters of The Industry Playbook can be found here.

You can also support this project with a tip.